Ergativity for Conlangers

A brief introduction to ergativity and a re-introduction to caseErgativity is a grammatical feature that is present in many languages around the world. According to WALS, 32 languages out of 190 represented in the database exhibit ergative-absolutive alignment in marking noun phrases; around 17% of languages. (This number is also an underestimate.) Despite being common in natural languages, many conlangers either have not implemented ergativity into their languages or do not understand ergativity. This is a tragedy! Ergativity is not any harder than accusativity, and it's a very deeply interesting feature. Even if your language does not end up exhibiting ergativity, understanding it can help you understand language as a whole more in-depth, as well as giving you ideas for how to make your language more interesting and more naturalistic. Firstly, we have to figure out what exactly we're talking about when we say "ergativity."

What is morphosyntactic alignment?

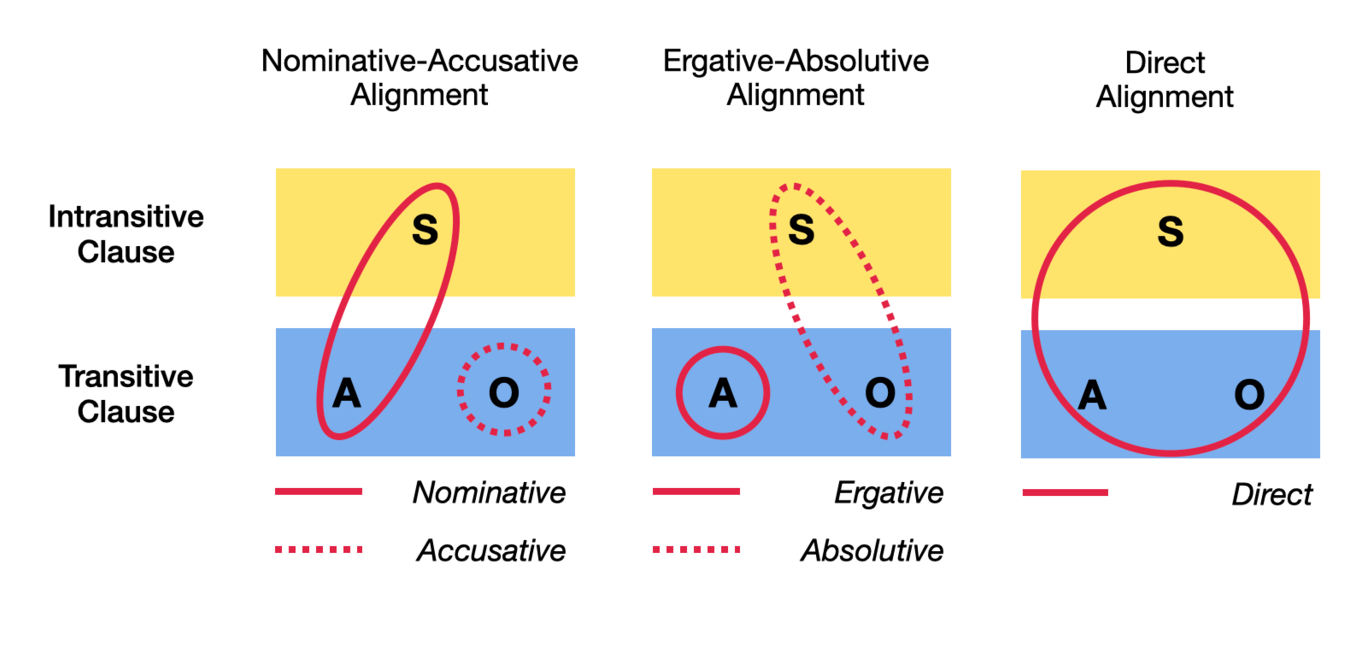

The first place to look is in the concept of morphosyntactic alignment. Morphosyntactic alignment is a property of languages which describes how the arguments of a verb are marked. There are, normally, three kinds of argument we're interested in in regards to morphosyntactic alignment.

- S, the subject of an intransitive verb (ones like "flow", "run", or "move"),

- A, the agent of a transitive verb (ones like "watch", "hug", or "eat"),

- P, the patient of a transitive verb. (Some authors also call this O for object.)

There are three main ways that languages mark these arguments: direct, nominative-accusative, and ergative-absolutive.

Direct alignment, nominative-accusative alignment, and ergative-absolutive alignment1

Direct alignment

This one is the easiest: just don't mark them differently at all! Unfortunately, this is also not very common. In my opinion, this is usually somewhat of a mischaracterisation as well - it would be somewhat difficult to prove that a language has an underlying direct alignment. Morphological direct alignment, however, is not very surprising. English, for example, could be argued to have a neutral alignment in full noun phrases, where neither the subject nor the object are marked for any sort of case. (Underlyingly, however, English is nominative-accusative.) WALS lists 21 languages with this alignment, including Mandarin and Vietnamese.

Nominative-accusative alignment

This is the alignment you are probably most familiar with. In this alignment, the subject of an intransitive verb and the agent of a transitive verb are marked the same way (usually called the nominative case), and the patient of a transitive verb is marked differently (usually called the accusative case). This is the alignment that English underlyingly has for noun phrases, as well as morphologically for pronouns, and is found in almost all Indo-European languages.

What exactly do I mean when I say "underlyingly"?

Some examples from German:

Here, we can see that the subject of the intransitive verb "renne" and the agent of the transitive verb "sehe" are marked identically. In both cases, we use the nominative case pronoun "ich". The patient of the transitive verb, however, is marked with the accusative case: "den Hund" instead of "der Hund".

Ergative-absolutive alignment

In contrast, ergative-absolutive alignment takes the other approach: identifying the patient of a transitive verb with the subject of an intransitive verb, and marking them the same way (usually called the absolutive case), while marking the agent of a transitive verb differently (usually called the ergative case).

We can see that Belhare marks the ergative case with a suffix -ŋa and doesn't mark the absolutive.3 This is textbook ergativity! This is where most treatments of ergativity end - with a simple explanation of ergative-absolutive alignment. However, this is not the end of the story - not in the slightest.

What about other kinds of alignments?

Yes, they exist, and they're very interesting! Unfortunately, I don't really have the time or knowledge to cover them. Wikipedia's coverage of them is okay (see their article on morphosyntactic alignment), but you should also take a look at The Typology of Semantic Alignment, by Mark Donohue and Søren Wichmann, which covers things like active-stative alignment in a much more in-depth manner.

What is an ergative language, really?

Saying a language uses an ergative-absolutive alignment is a bit of a simplication. The problem is that it doesn't really tell you very much about the language. Even so-called nominative-accusative languages can have ergative-like features:

Here, we see a marked subject and a less-marked object! This stands in opposition to its normal marking:

We can even find such behavior in such far-flung foreign languages as English! Consider the difference between the sentences "I broke the vase" and "The vase broke." Here, "break" could be said to be semantically ergative: the subject of the intransitive verb is patterning with the object of the transitive verb. Yet, we would never describe English as an ergative language (and it would in fact be somewhat odd to do so). The problem is that describing a language as having a certain alignment is usually not entirely useful. Many, many languages, perhaps all languages, that have case marking will exhibit ergative-like behavior in some contexts. Thus, we run into the problem that "ergative" is not a very useful label, or really even thing to talk about6. What matters a lot more is talking about how specific languages actually work!

What do languages that we normally call "ergative" look like?

Ergative marking can be a lot more interesting than just the bog-standard Dixon definition!

Split ergativity

This is probably the most familiar bit of "ergative weirdness" that you might know about. In split ergativity, there exists some line across which one kind of clause is marked ergatively and another is marked in a different way. However, in natural language there exists a lot of nuance about how exactly that forms!

In Coon (2013)7, the author goes over 3 different kinds of ergative splits: "ergative-to-neutral", "ergative-to-extended-ergative", and "ergative-to-ABS-OBL". Notably, "ergative-to-accusative" does not appear in this list! All of the patterns discussed here don't actually use any sort of nominative or accusative case in non-ergative clauses.

Ergative-to-neutral

This one is simple: in non-ergative clauses, neutral case marking occurs. In Basque, ergative marking occurs in perfective clauses, and neutral marking occurs in progressive clauses.

A more complex description

Coon believes that this sort of marking is actually part of the fact that the progressive marking in many languages is done through an auxiliary. We can then analyze the sentence as having a sort of embedded clause, in which fully-ergative marking is occurring:

Here, we could analyze the portion in square brackets as a separate clause. If we do that, then this marking is actually fully normal ergative marking!

Ergative to extended-ergative

In this case, we get a split where S and A are both marked ergatively. Coon's treatment of this is pretty short, unfortunately, but we have these examples from Chol:

Perfective

Progressive

We can see that in the progressive, the transitive sentence doesn't change much, but the intransitive sentence does! It ends up being marked similarly to a nominative/accusative system with the ergative filling the role of the nominative. This pattern is also perhaps explainable as an artifact of Chol's pervasive nominalization of verbs as well as its ergative marking being identical to its possessive marking - for more information, see the original paper.

Ergative to ABS-OBL

This pattern is probably the closest to a nominative-accusative system. In this pattern, an oblique case is used similarly to an accusative case in transitive sentences:

Notably, this pattern is known to occur across semantic boundaries, as well. In Adyghe (Northwest Caucasian; Russia), an ERG-ABS pattern occurs with the verb "kill" while an ABS-OBL pattern occurs with the verb "stab". Coon references a paper by Tsunoda in which the following generalizations can be made about where splits happen:

| Usually more ergative | Usually more non-ergative |

|---|---|

| action | state |

| impingement on P(atient) | non-impingement on P(atient) |

| P(atient) attained | P(atient) not attained |

| P(atient) totally affected | P(atient) partially affected |

| completed | uncompleted, or in progress |

| punctual | durative |

| telic | atelic |

| resultative | non-resultative |

| specific or single activity/situation | customary/general/habitual activity/situation |

| P(atient) definite/specific/referential | P(atient) indefinite/non-specific/non-referential |

While these aren't the only places where splits can occur (for example, person-based splits are very common), these generalizations tend to hold!

Syntactic ergativity

Syntactic ergativity is somewhat controversial, but it's very interesting. While most of this document has focused on morphological ergativity, various languages exhibit features of ergativity within their syntax.

Ergative inter-clausal syntax

While rare, some languages exhibit ergative syntax in inter-clausal syntax. The best example comes from Dyirbal, one of the most famous ergative languages. When connecting two clauses with a conjunction, Dyirbal exhibits ergative syntax. The first sentence is the more normal reading, and shows that by default, the absolutive argument is the one shared between clauses:

and in order to get a more English-like reading, where you can say "father returned and saw mother", you have to make use of an antipassive construction:

An antipassive construction promotes the ergative argument to the absolutive and makes the original absolutive argument an oblique argument, similar to how the passive voice works in accusative languages.

Relative clauses

An important part of relative clauses is what exactly can be relativised. English is extremely permissive, but many languages restrict what arguments can be relativised. In general, in accusative languages, the acccessibility hierarchy runs as follows9, with items listed first being "easier" to relativise:

- Subject

- Direct object

- Indirect object

- Oblique

- Genitive

- Object of comparison (e.g. "the woman who I am taller than")

However, in some languages which exhibit ergative marking, we see a hierarchy that looks like this:

- Absolutive

- Ergative

- Indirect object

- (...etc)

In her paper on syntactic ergativity, Maria Polinsky gives an example from Chukchi, in which the antipassive construction we briefly looked at in the last section is used to relativise ergative arguments. The first example here is a normal transitive sentence:

and then its antipassive form:

and finally, the manner by which you would relativise either of these sentences:

By using the antipassive, Chukchi speakers can relativise ergative arguments that are otherwise inaccessible. Other languages, like Inuit (Eskaleut; Canada, Greenland) and Roviana (Austronesian; Solomon Islands) use nominalization strategies.

What about languages with syntactic ergativity, but no morphological ergativity?

Simple answer: we don't know of any! Polinsky (2017) investigated this phenomenon and also found it pretty odd, considering there's no theoretical barriers to a language like this existing that we know of. A couple languages get close - French, for example, has a somewhat ergative pattern in causative structures which almost suggests syntactic ergativity, but when you put it in an interrogative sentence, you find that their structures underlyingly pattern accusatively. If you make a language like this and do much theoretical basis with it, I'd love to hear about it!

Discourse ergativity

This one is less familiar to me, so I'll have to point you to other papers, but it's very interesting! In some languages, the shape of discourse - the way we use language itself - can be structured in an ergative manner11. These languages prefer to present new information as Actors (our S role) or Undergoers (our P role), rather than as Agents (our A role). This was originally observed in Sacapultec (Mayan; Guatemala), but has been found in many other languages, even including accusative languages like Hebrew. For more information, see the cited work in McGregor's Typology of Ergativity.

How can we implement ergativity in interesting ways like this?

In order to implement ergativity, some intuitive knowledge of how ergativity works on a base level is necessary. This is a bit of a big topic, and it might be easier to just take a look at some of the phenomena we looked at earlier - but understanding how case assignment works will help you understand how to make constructed languages that are more naturalistic, more original, and more interesting!

How does case really work?

While this is a complex and highly-debated topic, we'll take the system presented in Clem and Deal (2024)[^clemdeal] as a base for this explanation.

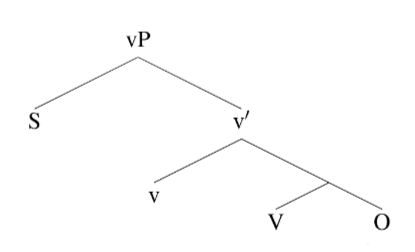

Our syntax tree

The central part of all of this is our base verb phrase syntax tree. While you don't need to fully understand it, this is the shape of the tree that we believe in:

Here, we have

- vP, the "little v phrase", which is kind of like an extended verb phrase

- S, our subject

- v, or "little v", which is usually a semantically-light contrivance of the tree

- V, our main verb

- O, the object

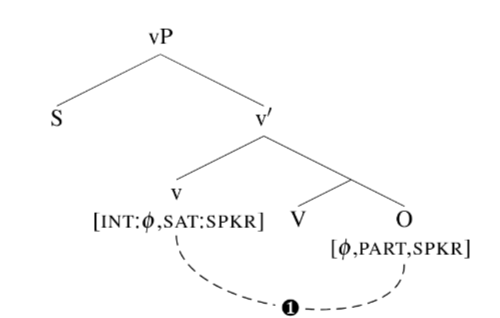

The AGREE probe

In order to make verbs agree with their arguments, we have an operation called AGREE. This operation

- starts from v,

- attempts to find an argument to agree with within its domain (any sisters of v or their daughters),

- if it doesn't find an argument:

- it merges with the higher tree, and keeps going (until it hits a complementizer or something),

- if it does find an argument:

- it either interacts with the argument or is satisfied by it

Interaction and satisfaction

An AGREE probe will be satisfied by an argument if the argument has features which are listed in

the probe's satisfaction feature list.

AGREE probe is satisfied by SPKR, the first person feature, and stops probingIf the argument instead has features which are listed in the probe's interaction feature list, the probe is modified by the argument:

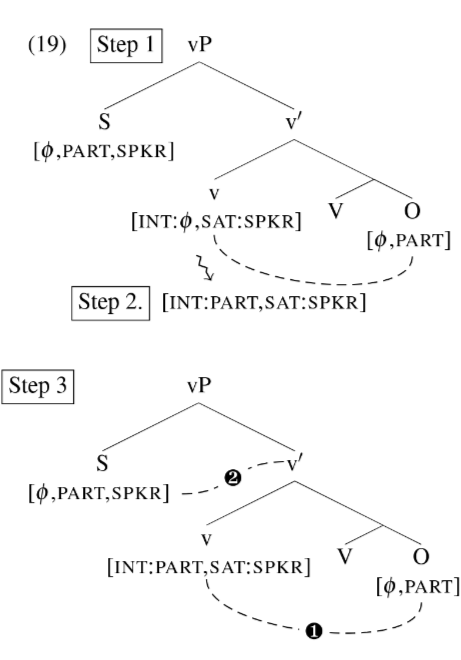

AGREE probe is modified by the feature ERG on the object, and is satisfied by subjInteraction is not very particular - you should understand it primarily from a configurational perpsective where different languages are known to have different paradigms. Here, we see that where originally, the probe would interact with any given φ feature, it now remembers that it interacted with the PART feature (meaning second person).

Case assignment

How does this exactly help us with case? Well, different languages will have different ways of assigning case to different probe results.

According to Clem and Deal, the way that accusative languages work is that a probe from T (our tense portion) agrees with the subject, and then the object. In the second agreement, the probe "remembers" that it has already interacted with a subject, and assigns accusative case! Ergative languages can be explained by a v probe which interacts with the object first, expands, and then is satisfied by the subject. This model can explain all sorts of patterns, from differential object marking, to split ergativity, as well as tying case marking in with verbal agreement. If you want more examples of how this system can be used to explain other languages, you should take a look at the paper itself. It's less scary than it seems!

Conclusion

Ergativity is a very interesting and complex topic, but it's not impossible to understand. By understanding the ways in which languages exhibit ergative patterns, you can make your languages more interesting and more naturalistic. In this article, you learned about the ways in which our usual definition of ergativity is somewhat lacking, how languages we normally call ergative really work, and how you can implement ergativity in your own languages. I hope you found this article informative and interesting!

How can we research other areas of language like this?

By Votre Idéolinguiste Local - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=135265037

Bickel, B. & Nichols, J. (2009). Case marking and alignment. In A. Malchukov & A. Spencer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Case (pp. 304-321). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

The original source marks this as nominative, but I think this is due to their more in-depth analysis. For the purposes of this article, I'm marking it as absolutive - the point, anyways, is that the object of the transitive verb patterns with the subject of the intransitive verb.

Ura, Hiroyuki. (2000). Checking theory and grammatical functions in Universal Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Via José-Luis Mendívil-Giró. (2012) Ergativity as transitive unaccusativity. Folia Linguistica, vol. 46, no.. 1, 2012, pp. 171-210)

Tsujimura, Natsuko (2007). An introduction to Japanese linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-4051-1065-5.

For a much more in-depth version of this argument, read The Blue Bird of Ergativity.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. TAM split ergativity. Language and Linguistics Compass 7:171–200.

Originally, this was glossed as "The boy spotted the fish" versus "The boy looked at the fish". These are probably more faithful translations, but are less useful for the purpose of showing off the aspectual distinction.

Keenan, Edward L.; Comrie, Bernard (1977). "Noun phrase accessibility and Universal Grammar". Linguistic Inquiry. 8 (1): 63–99.

I'm unsure how to translate an antipassive very well. I'm somewhat tempted to say "the gun was bought by the old man", but that puts a bit too much emphasis on "the gun", which certainly isn't what's supposed to be interpreted with this sentence!

McGregor, W.B. (2009), Typology of Ergativity. Language and Linguistics Compass, 3: 480-508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00118.x

Clem, Emily and Amy Rose Deal. 2024. Dependent case by Agree: Ergative in Shawi. to appear in Linguistic Inquiry.